Why transfer prices are needed

Transfer prices are almost inevitably needed whenever a business is divided into more than one department or division. Usually, goods or services will flow between the divisions, and each will report its performance separately. The accounting system will record goods or services leaving one department and entering the next, and some monetary value must be used to record this. That monetary value is the transfer price.

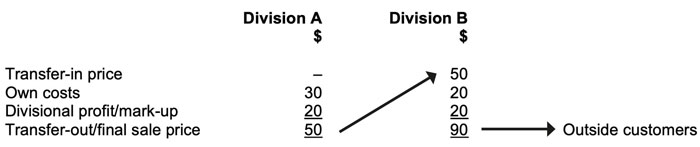

Take the following scenario shown in Table 1, in which Division A makes components for a cost of $30, and these are transferred to Division B for $50. Division B buys the components in at $50, incurs own costs of $20, and then sells to outside customers for $90.

Table 1 Example 1

As things stand, each division makes a profit of $20/unit, and the company will make a profit of $40/unit. This can be calculated either by simply adding the two divisional profits together ($20 + $20 = $40) or subtracting both own costs from final revenue ($90 – $30 – $20 = $40).

It is important to see that for every $1 increase in the transfer price, Division A will make $1 more profit, and Division B will make $1 less. Mathematically, the company will make the same profit, but these changing profits can result in each division making different decisions, and as a result of those decisions, company profits might be affected.

The transfer price set should encourage divisions to trade in a way that maximises profits for the company as a whole.

A transfer price can be negotiated between the divisions or imposed by head office. In a Performance Management (PM) question, a requirement could be to calculate and discuss the impact of a head office imposed transfer price, or to suggest transfer prices which would be acceptable to each division.

It is important to understand that there is no one right transfer price in a given scenario, but there will be alternative legitimate views with some values being more appropriate or more acceptable than others.

The impact of transfer prices

Transfer prices can seriously affect the reported divisional performance, the motivation of divisional managers and subsequent decisions made.

Performance evaluation

The transfer price affects the profit that a division makes. In turn, the profit is often a key figure used when assessing the performance of a division. This will certainly be the case if return on investment (ROI) or residual income (RI) is used to measure performance.

A higher transfer price will lead to lower profits in the buying division and make its performance look poorer than it would otherwise be. The selling division, on the other hand, will appear to be performing better. A lower transfer price on the other hand will favour the buying division.

This may lead to poor decisions being made by the company. The management of the company could interpret these measures as indicating that a division’s performance was unsatisfactory and could decide to reduce investment in that division, or even close it down.

Performance-related pay

If there is a system of performance-related pay, the remuneration of employees in each division will be linked to the performance of the division and this will be affected as profits change. If divisional performance is poor because of something that the manager and staff cannot control, such as being forced to trade internally or to use head office set transfer prices, and as a result they are consequently paid a smaller bonus for example, they are going to become unhappy and frustrated. This could seriously damage their morale and could lead to a lack of motivation to do the job well which could have a knock-on effect on the real performance of the division. As well as being seen not to do well because of the impact of high transfer prices on ROI and RI, the division really will perform less well.

In a PM question it is important to be able to discuss how transfer prices can affect performance assessment of divisions, motivation and decision making. Further impacts of transfer prices will be considered in Advanced Performance Management (APM), but these points are sufficient for the level of understanding needed for the PM exam.

The characteristics of a good transfer price

Although not easy to attain simultaneously, a good transfer price should:

Preserve divisional autonomy: almost inevitably, divisionalisation is accompanied by a degree of decentralisation in decision making so that specific managers and teams are put in charge of each division and must run it to the best of their ability.

If divisional managers have the objective of maximising divisional profit, they are likely to resent being told by head office that they must trade internally at an imposed price when they could generate higher profits by buying or selling externally.

However, allowing divisions to be totally autonomous, could reduce the company profit at the expense of the divisional profit.

Encourage divisions to make decisions which maximise group profits: the transfer price will achieve this if the decisions which maximise divisional profit also happen to maximise group profit – this is known as goal congruence. Furthermore, all divisions must want to do the same thing. There’s no point in transferring divisions being very keen on transferring out if the next division doesn’t want to transfer in.

Permit each division to make a profit: profits are motivating and allow divisional performance to be measured using positive ROI or positive RI. Some transfer prices, however, can favour one division over another and can make it difficult for divisions to earn a profit. This is unfair if divisional performance and bonuses are based on profit measurements.

Setting a transfer price

Let us now consider the general principles of setting a transfer price. There are several approaches which should be recognised.

Cost based approaches

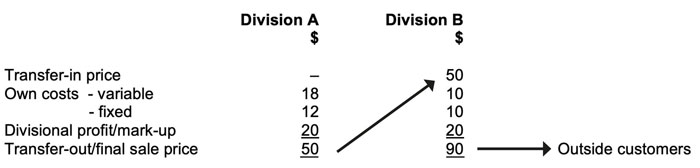

In the following examples, assume that Division A can sell only to Division B, and that Division B can only buy from Division A. Example 1 has been reproduced but with costs split between variable and fixed. At the transfer price of $50 given, this allows each division to make a profit of $20.

Table 1 Example 2

Variable cost

A transfer price set equal to the variable (marginal) cost of the transferring division produces very good economic decisions. If the transfer price is $18, Division B’s marginal costs would be $28 (each unit costs $18 to buy in then incurs another $10 of variable cost). The company’s marginal costs are also $28, so there will be goal congruence between Division B’s wish to maximise its profits and the company maximising its profits. If marginal revenue exceeds marginal costs for Division B, it will also do so for the company.

Although good economic decisions are likely to result, a transfer price equal to marginal cost has certain drawbacks:

Division A will make a loss as its fixed costs cannot be covered. This is demotivating for Division A’s management.

Performance measurement is also distorted. Division A will make a loss while Division B is in more fortunate position as it is not charged enough to cover all costs of manufacture. This effect can also distort investment decisions made in each division. For example, Division B will enjoy inflated cash inflows.

There is little incentive for Division A to be efficient if all marginal costs are covered by the transfer price. Inefficiencies in Division A will be passed on to Division B.

Table 1 Example 3

Full cost/Full cost plus/Variable cost plus

A transfer price set at full cost, as shown in Table 3 is slightly more satisfactory for Division A as it means that it can aim to break even. Its big drawback, however, is that it can lead to dysfunctional decisions because Division B can make decisions that maximise its profits, but which will not maximise company profits. For example, if the final market price fell to $35, Division B would not trade because its marginal cost would be $40 (transfer-in price of $30 plus own marginal costs of $10). However, from a group perspective, the marginal cost is only $28 ($18 + $10) and a positive contribution would be made even at a selling price of only $35. Head office could, of course, instruct Division B to trade but then divisional autonomy is compromised, and Division B managers will resent being instructed to make negative contributions which will impact on their reported performance.

The full cost plus approach would increase the transfer price by allowing division A to add a mark-up. This would now motivate Division A, as profits can be made there and may also allow profits to be made by Division B. However, again this can lead to dysfunctional decisions as the final selling price falls.

Once you move away from a transfer price equal to the variable cost in the transferring division, there is always the risk of dysfunctional decisions being made unless an upper limit – equal to the net marginal revenue in the receiving division – is also imposed.

Where there is a market for the intermediate product

The setting of a transfer price is complicated where there is an external market for the product – ie where the selling division can sell the product externally, and, or the buying division can buy the product externally. Always read the scenario carefully in a transfer pricing question to find out if the product being transferred can be sold or bought externally as this can affect the transfer price which should be set.

Consider Example 1 again, where the transfer price had been set at $50, but this time assume that the intermediate product can be sold to, or bought from, the market at a price of $40.

Division A would rather transfer internally to Division B, because receiving $50 is better than receiving $40. However, Division B would rather buy externally at the cheaper price of $40. If Division B buys externally, this would be bad for the company because there is now a marginal cost to the company of $40 instead of only $18 (the variable cost of production in Division A).

In an exam question, it is important to be able to discuss this type of situation. It can be useful to consider the minimum and maximum transfer prices that each division would accept. In discussing transfer prices, think about:

- What would the selling division prefer to do and how would this affect the buying division and the company?

- What would the buying division prefer to do and how would this affect the selling division and the company?

Minimum transfer price

When considering the minimum transfer price, look at transfer pricing from the point of view of the selling division. The question we ask is: what is the minimum selling price that the selling division would be prepared to sell for? Note that this will not necessarily be the same as the price that the selling division would be happy to sell for, although, as you will see, if it does not have spare capacity, it is the same.

The minimum transfer price that should be set if the selling division is to be happy is:

marginal cost + opportunity cost.

Opportunity cost is defined as the 'value of the best alternative that is foregone when a particular course of action is undertaken'. Given that there will only be an opportunity cost if the seller does not have any spare capacity, the first question to ask is therefore: does the seller have spare capacity?

Spare capacity

If there is spare capacity, then, for any sales that are made by using that spare capacity, the opportunity cost is zero. This is because workers and machines are not fully utilised. So, where a selling division has spare capacity the minimum transfer price is effectively just marginal cost. However, this minimum transfer price is probably not going to be one that will make the managers happy as they will want to earn additional profits. So, you would expect them to try and negotiate a higher price that incorporates an element of profit.

No spare capacity

If the seller doesn’t have any spare capacity, or it does not have enough spare capacity to meet all external demand and internal demand, then the next question to consider is: how can the opportunity cost be calculated? Given that opportunity cost represents contribution foregone, it will be the amount required in order to put the selling division in the same position as they would have been in had they sold outside of the group.

Logically, the buying division must be charged the same price as the external buyer would pay, less any reduction for cost savings that result from supplying internally. These reductions might reflect, for example, packaging and delivery costs that are not incurred if the product is supplied internally to another division.

It is not really necessary to start breaking the transfer price down into marginal cost and opportunity cost in this situation, it can simply be calculated as the external market price less any internal cost savings.

At this transfer price, the selling division would make just as much profit from selling internally as selling externally. Therefore, it reflects the price that they would actually be happy to sell at. They should not expect to make higher profits on internal sales than on external sales.

Maximum transfer price

When we consider the maximum transfer price, we are looking at transfer pricing from the point of view of the buying division. The question we are asking is: what is the maximum price that the buying division would be prepared to pay for the product? The answer to this question is very simple and the maximum price will be one that the buying division is also happy to pay.

The maximum price that the buying division will want to pay is the market price for the product – ie whatever they would have to pay an external supplier. If this is the same as the selling division sells the product externally for, the buyer might reasonably expect a reduction to reflect costs saved by trading internally.

In an exam answer, be willing to discuss the minimum and maximum transfer prices and how each division would react to them.

Summary

The level of detail given in this article reflects the level of knowledge required for Performance Management. It is important to understand the purpose of transfer pricing, its impact on performance measurement, motivation and decision making and to be able to work out a reasonable transfer price/range of transfer prices.

Written by a member of the Performance Management examining team