Ken Garrett demystifies activity-based costing and provides some tips leading up to the all-important exams

Conventional costing distinguishes between variable and fixed costs. Typically, it is assumed that variable costs vary with the number of units of output (and that these costs are proportional to the output level) whereas fixed costs do not vary with output. This is often an over-simplification of how costs actually behave. For example, variable costs per unit often increase at high levels of production where overtime premiums might have to be paid or when material becomes scarce. Fixed costs are usually fixed only over certain ranges of activity, often stepping up as additional manufacturing resources are employed to allow high volumes to be produced.

Variable costs per unit can at least be measured, and the sum of the variable costs per unit is the marginal cost per unit. The marginal cost is the additional costs caused when one more unit is produced. However, there has always been a problem dealing with fixed production costs such as factory rent, heating, supervision and so on. Making a unit does not cause more fixed costs, yet production cannot take place without these costs being incurred. To say that the cost of producing a unit consists of marginal costs only will understate the true cost of production and this can lead to problems. For example, if the selling price is based on a mark‑up on cost, then the company needs to make sure that all production costs are covered by the selling price. Additionally, focusing exclusively on marginal costs may cause companies to overlook important savings that might result from better controlled fixed costs.

Absorption costing

The conventional approach to dealing with fixed overhead production costs is to assume that the various cost types can be lumped together and a single overhead absorption rate derived. The absorption rate is usually presented in terms of overhead cost per labour hour, or overhead cost per machine hour. This approach is likely to be an over-simplification, but it has the merit of being relatively quick and easy.

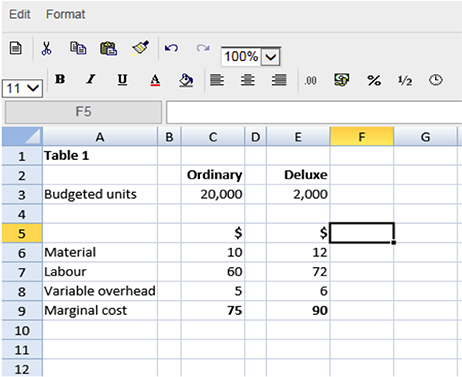

Example 1

In Table 1 in the spreadsheet above, we are given the budgeted marginal cost for two products. Labour is paid at $12 per hour and total fixed overheads are $224,000. Fixed overheads are absorbed on a labour hour basis.

Based on Table 1 the budgeted labour hours must be 112,000 hours. This is derived from the budgeted outputs of 20,000 Ordinary units which each take five hours (100,000 hours) to produce, and 2,000 Deluxe units which each take six hours (12,000 hours).

Therefore, the fixed overhead absorption rate per labour hour is $224,000/112,000 = $2/hour.

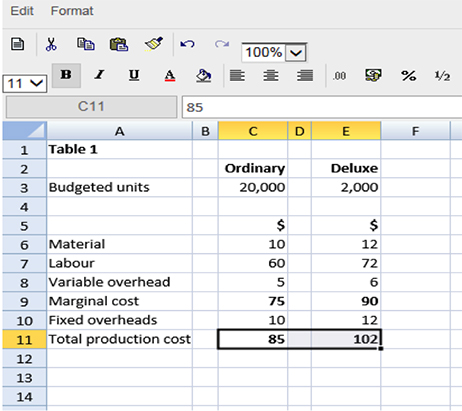

The costing of the two products can be continued by adding in fixed overhead costs to obtain the total absorption cost for each of the products.

Table 1 has been amended to include the fixed overheads to be absorbed in both products.

Ordinary: (5 labour hours x $2 OAR) = $10

Deluxe: (6 labour hours x $2 OAR) = $12

This means we have arrived at the total production cost for both products under absorption costing. It also tell us that if production goes according to budget then total costs will be (20,000 x $85) + (2,000 x $102) = $1,904,000.

The conventional approach outlined above is satisfactory if the following conditions apply:

- Fixed costs are relatively immaterial compared to material and labour costs. This is the case in manufacturing environments which do not rely on sophisticated and expensive facilities and machinery.

- Most fixed costs accrue with time.

- There are long production runs of identical products with little customisation.

However, much modern manufacturing relies on highly automated, expensive manufacturing plants – so much so that some companies do not separately identify the cost of labour because there is so little used. Instead, factory labour is simply regarded as a fixed overhead and added in to the fixed costs of running the factory, its machinery, and the sophisticated information technology system which coordinates production.

Additionally, many companies rely on customisation of products to differentiate themselves and to enable higher margins to be made. Dell, for example, a PC manufacturer, has a website which lets customers specify their own PC in terms of memory size, capacity, processor speed etc. That information is then fed into their automated production system and the specified computer is built, more or less automatically.

Instead of offering customers the ability to specify products, many companies offer an extensive range of products, hoping that one member of the range will match the requirements of a particular market segment. In Example 1, the company offers two products: Ordinary and Deluxe. The company knows that demand for the Deluxe range will be low, but hopes that the price premium it can charge will still allow it to make a good profit, even on a low volume item. However, the Deluxe product could consume resources which are not properly reflected by the time it takes to make those units.

These developments in manufacturing and marketing mean that the conventional way of treating fixed overheads might not be good enough. Companies need to know the causes of overheads, and need to realise that many of their ‘fixed costs’ might not be fixed at all. They need to try to assign costs to products or services on the basis of the resources they consume.

Activity-based costing

What we want to do is to get a more accurate estimate of what each unit costs to produce, and to do this we have to examine what activities are necessary to produce each unit, because activities usually have a cost attached. This is the basis of activity-based costing (ABC).

The old approach of simply pretending that fixed costs are incurred because of the passage of time, and that they can therefore be accounted for on the basis of labour (or machine) time spent on each unit, is no longer good enough. Diverse, flexible manufacturing demands a more accurate approach to costing.

The ABC process is as follows:

- Split fixed overheads into activities. These are called cost pools.

- For each cost pool identify what causes that cost. In ABC terminology, this is the ‘cost driver’, but it might be better to think of it as the ‘cost causer’.

- Calculate a cost per unit of cost driver (Cost pool/total number of cost driver).

- Allocate costs to the product based on how much the product uses of the cost driver.

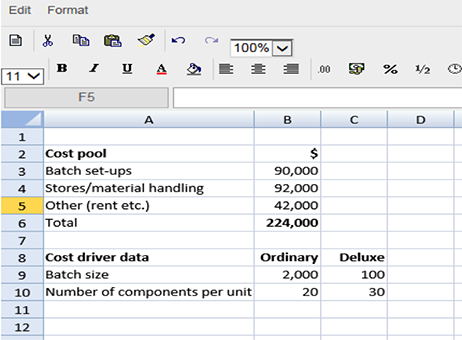

Let’s continue with our example from earlier; the total fixed overheads were $224,000. In the table below in Example 2 the total overheads have been split into cost pools and cost driver data for the Ordinary and Deluxe products has been collated.

Example 2

If we apply the ABC process we can see that Step 1 is complete as we know what the cost pools are.

For Step 2 we need to identify the cost driver for each cost pool.

Batch set-up costs will be driven by the number of set-ups required for production:

Ordinary: 20,000/2,000 = 10

Deluxe units: 2,000/100 = 20

Total set-ups: 30

Stores/material handling costs will be driven by the number of components required for production:

Ordinary: (20,000 units x 20) = 400,000

Deluxe: (2,000 units x 30) = 60,000

Total components = 460,000

Other fixed overheads will have to be absorbed on a labour hour basis because there is no information provided which would allow a better approach. We know from Example 1 that total labour hours required are 112,000.

In Step 3 we need to calculate a cost per unit of cost driver.

Batch set-ups:

$90,000/30 = $3,000/set-up

Stores/material handling:

$92,000/460,000 = $0.20/component

Other overheads:

$42,000/112,000 = $0.375/labour hour

Step 4 then requires us to use the costs per unit of cost driver to absorb costs into each product based on how much the product uses of the driver.

Batch set-ups:

Ordinary: ($3,000/2,000 units) = $1.50/unit

Deluxe: ($3,000/100 units) = $30/unit

Store/material handling:

Ordinary: ($0.20 x 20 components) = $4/unit

Deluxe: ($0.20 x 30 components) = $6/unit

Other overheads:

Ordinary: ($0.375 x 5 hours) = $1.875/unit

Deluxe: ($0.375 x 6 hours) = $2.25/unit

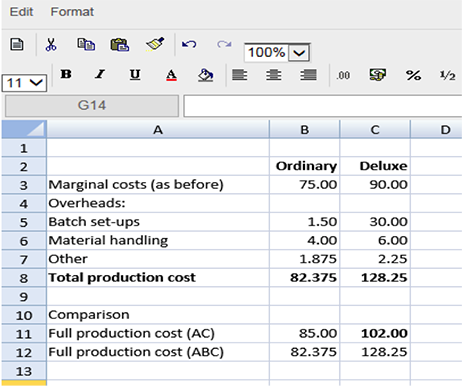

The ABC approach to costing therefore results in the figures shown in the spreadsheet below.

Check:

If production goes according to budget total costs will be (20,000 x $82.375) + (2,000 x $128.25) = $1,904,000

If you look at the comparison of the full cost per unit in the spreadsheet above, you will see that the ABC approach substantially increases the cost of making a Deluxe unit. This is primarily because the Deluxe units are made in small batches. Each batch causes an expensive set-up, but that cost is then spread over all the units produced in that batch – whether few (Deluxe) or many (Ordinary). It can only be right that the effort and cost incurred in producing small batches is reflected in the cost per unit produced. There would, for example, be little point in producing Deluxe units at all if their higher selling price did not justify the higher costs incurred.

In addition to estimating more accurately the true cost of production, ABC will also give a better indication of where cost savings can be made. Remember, the title of this exam is Performance Management, implying that accountants should be proactive in improving performance rather than passively measuring costs. For example, it’s clear that a substantial part of the cost of producing Deluxe units is set-up costs (almost 25% of the Deluxe units’ total costs).

Working on the principle that large cost savings are likely to be found in large cost elements, management’s attention will start to focus on how this cost could be reduced.

For example, is there any reason why Deluxe units have to be produced in batches of only 100? A batch size of 200 units would dramatically reduce those set-up costs.

The traditional approach to fixed overhead absorption has the merit of being simple to calculate and apply. However, simplicity does not justify the production and use of information that might be wrong or misleading.

ABC undoubtedly requires an organisation to spend time and effort investigating more fully what causes it to incur costs, and then to use that detailed information for costing purposes. But understanding the drivers of costs must be an essential part of good performance management.

Ken Garrett is a freelance writer and lecturer