Guidance on Internal Audit planning and strategy

For the past 14 years, James Paterson has been consulting and running training courses on internal audit planning and developing an audit strategy. This article summarises common misunderstandings, typical good practice, and key points for the future.

A common misunderstanding: Internal Audit (IA) does the checking

When you go back in time, it’s easy to understand how an IA played a role in ensuring things are under control (“Can you check the stock in the warehouse?”) or in compliance with laws and regulations (“Will we be OK if the regulator comes to check our data privacy compliance?”). The logic was that senior management, or the board, might be worried about an area, and then ask for IA to check what’s happening. This might work for a while, but after a period you can end up with an organisation that thinks “internal audit is the one that does the double-checking.”

But 99.9% of the time you can’t get IA to check everything. So, if you are about to make a payment to a supplier, and are concerned about potential fraud, you need the accounts department to check the invoice is legitimate and that the bank account details provided are correct. No amount of internal audits after the event, will stop a fraud.

And if you did try to place this responsibility on IA you would rapidly find:

- IA doesn’t have enough resource

- It would slow down business activities to be involved all the time and – perhaps most important of all

- Staff and managers would start to pay less attention to keeping things ‘in control’ for themselves, thinking “Internal Audit will check that, so why should I worry?”

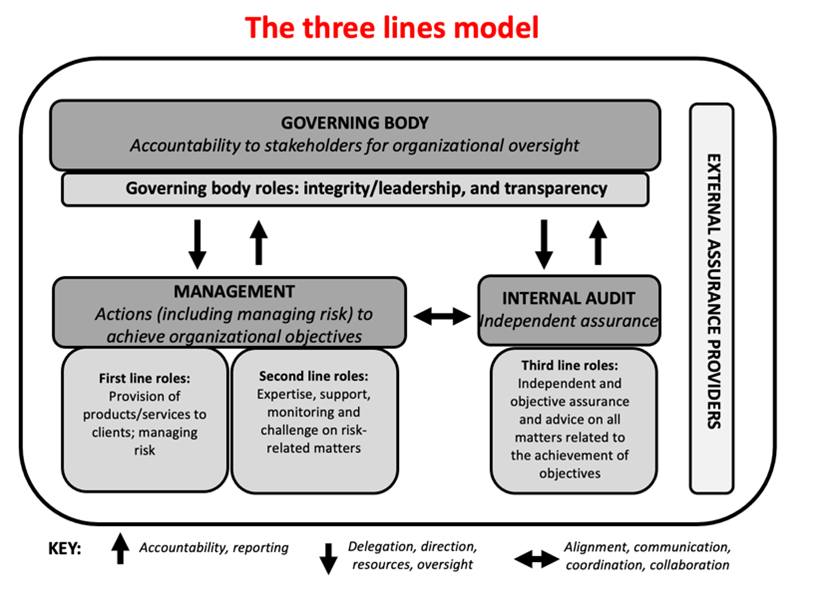

The three lines model

As a result, the Institute of Internal Audit (IIA) developed a framework called the ‘three lines model’ that makes it clear that it is the role of staff and managers (in the first line) and specialist functions (e.g., Finance, IT, Legal etc., in the second line) to set objectives (approved by governance bodies such as the board) and then to put in place processes and procedures that ensure that these goals are met and that any risks are managed to within agreed limits.

This means that the first and second lines need to check what they are doing as they go, and report any key problems upwards in real time, not after the event. Cyber security threats are a great example where risks must be proactively managed by the first and second line, after all a hacker isn’t going to wait around to instal malware at the time of an internal audit, they are looking out for weaknesses all the time.

So, internal audit comes in as a third line to provide advice or assurance to senior management and the board on selected key risk areas of particular importance, but not simply to be a substitute for what should already be happening in the first and second lines.

This is set out in the following ‘three lines’ diagram, promoted by the IIA:

-

Internal Audit: Risk Assurance that adds value and offers insight

Over time, for all the reasons explained earlier, it was established that IA should develop risk-based audit plans. The logic is simple, with limited resources it’s not possible for IA to look at everything. It needs to look at the most important areas where additional advice and assurance is needed.

Subsequently, IIA standards promoted two other key practices to ensure IA plans were optimised:

- Audit plans should be aligned with the strategies, objectives and risks of the organisation. The message here is that something might not be classified as a key risk, but nonetheless be an important strategic priority and – for that reason – should be high on the list for consideration for additional assurance or advice by IA.

- Audit plans should consider assurance provided by others, potentially relying on others and certainly co-ordinating with them. This is obvious, but still poorly understood by many managers. If you have an excellent cyber security programme, run by a very competent CISO, why would you do repeat internal audits, when they are (perhaps) already doing a good job?! If the compliance team have just reviewed an area, why would you do an internal audit ‘from scratch,’ as if they hadn’t done any work?

So, the message for internal audit planning should be clear:

- Look at the objectives and risks that matter the most,

- Consider other assurances and how much they can be relied upon (which is a topic in its own right), and then,

- Develop an internal audit plan that maximises the chances of IA assignments that are value adding and insightful.

-

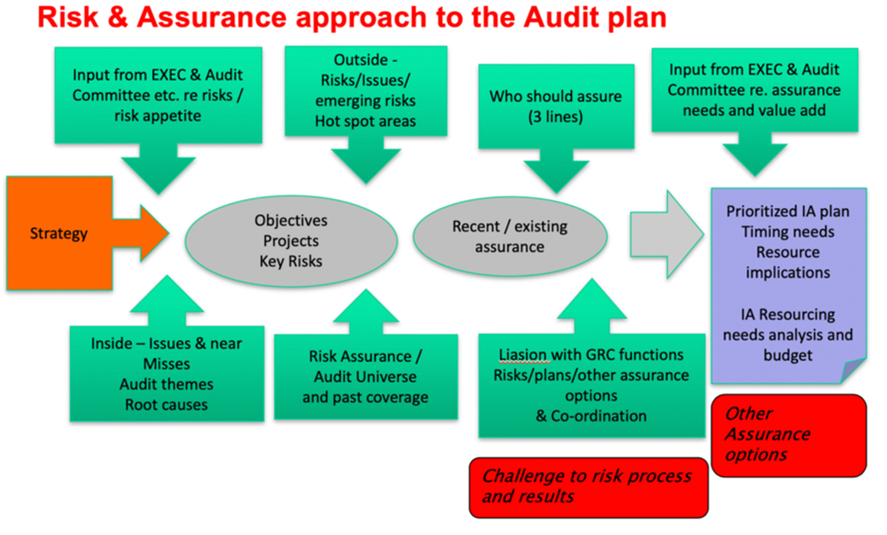

An overview of an internal auditing planning process

The new IIA Global Internal Audit Standards (GIAS) require that IA should spell out explicitly how the IA planning process works. I was involved in developing a process overview that is summarised in the IIA guidance on risk-based audit planning, but in my consulting and training work, I have developed the attached process overview, which provides some more granularity on the IA planning process.

Notice that:

- Internal incidents/issues/losses or near misses and external “hot spot” areas of concern should be considered, to ensure any IA plan is in tune with latest areas of concern.

- The audit planning process regards an audit universe as one input to the planning process, not as the driver of the plan.

- Other assurances should be a key consideration; after all, why should IA audit a project or programme when there is already a consultant or programme management office involved?

- Sometimes it makes sense to ask first or second line managers (or external consultants) to provide direct assurance to senior management and/or the board on an area of concern. And after that, decide what additional assurance or advice is needed from IA that will add value?

- IA services can include advisory assignments, not just audit and assurance assignments. For example, in the early days of a project it’s far easier (and adds more value) to advise on the project plans before there is anything to audit, rather than after the event.

- It is quite appropriate that an IA plan might be updated on a regular basis (e.g., every few months) as circumstances change. Long gone are the days since IA would develop a plan in one year and then stick to it for the next 12-15 months.

- It can be helpful to consider the potential scope and objectives of any IA assignment during the IA planning process. You can do this by asking what are the likely exam question(s) that need to be addressed, that will really add value (and not just repeat what is already known), if IA does work in this area?

-

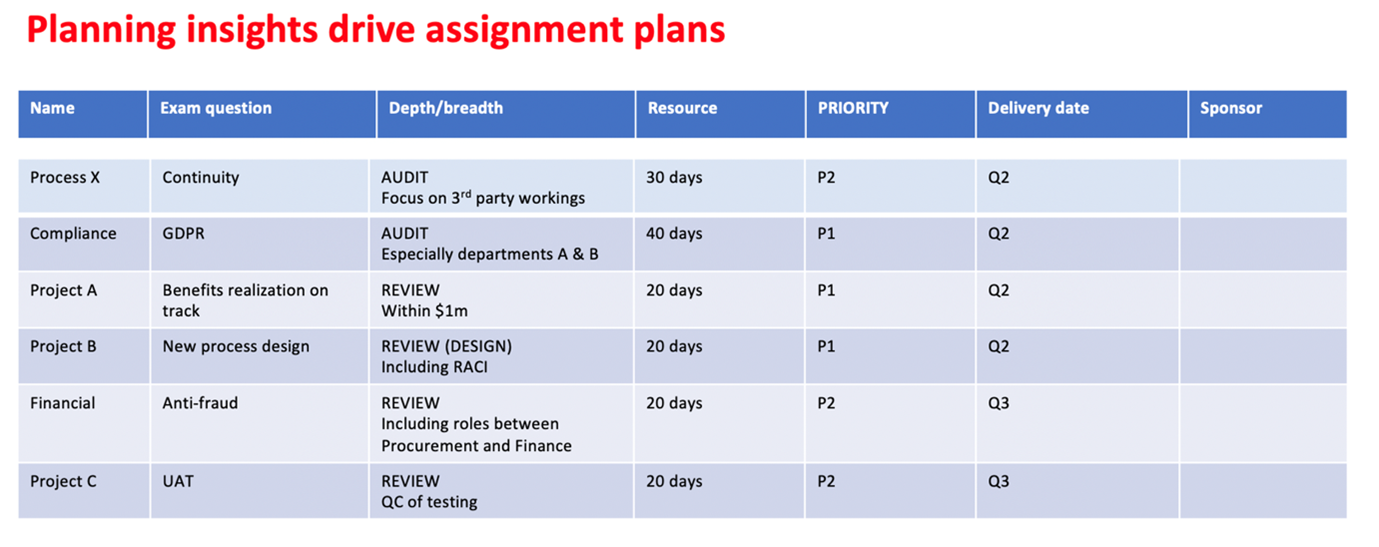

Create a golden thread between the IA plan and IA assignments

Thinking about potential assignments as a part of the IA planning process is invaluable because it helps to clarify key skills that may be required to deliver an assignment (i.e., to answer a specific exam question), and the likely timing requirements. This level of detail also helps the IA team better estimate the likely resource budget (based on a consideration of the likely depth and breadth of any proposed assignment) as well as its relative priority (which may be useful when considering if assignments can be cancelled or postponed). It will also maximise the chances that any assignment focuses on issues of real importance to senior managers or other key stakeholders, reducing the chances that someone will say “Why did you spend all that time on that area, it’s not that important?”

Use the audit planning process to raise awareness of improvement potential in governance, risk and control/compliance (GRC) activities. After all, if internal audit assignments are regularly wanted in areas that keep going off track (e.g. in project delivery or procurement), could it be that there is an underlying problem in the quality of first line risk identification or first- and second-line monitoring, that explains the need for ongoing or increasing IA involvement?

-

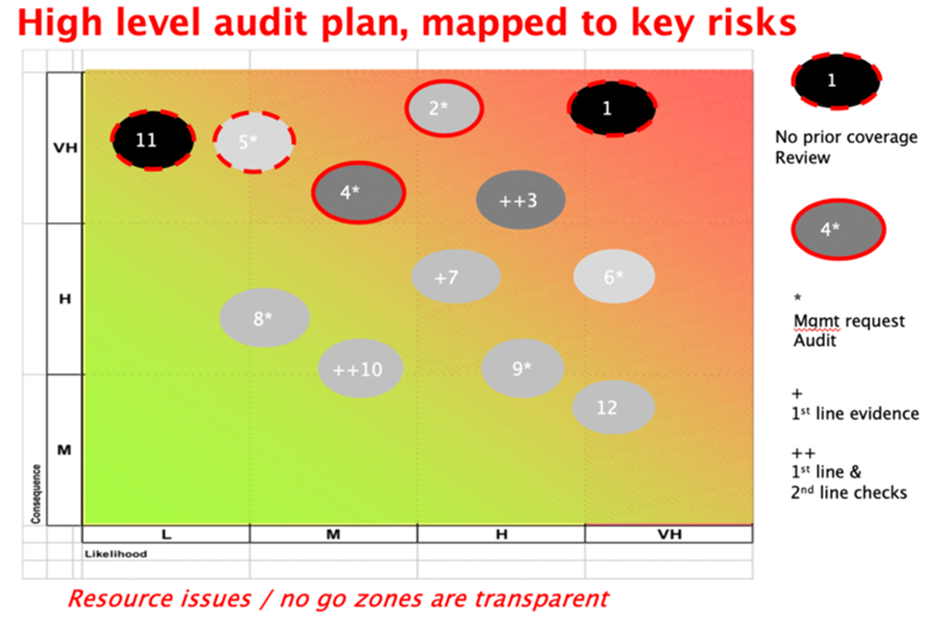

Other good practice of note

- Recognise that whilst an audit universe can be a useful input to an internal audit plan, it can take a great deal of time and effort to build an audit universe and keep it up to date, with sophisticated calculations and often arbitrary weightings to risk rate all its elements. Instead, use a risk/audit/assurance universe to keep track of past and planned audits and assurances, but be wary of creating an industry in keeping it up to date with micro analyses of every ingredient.

- Make it crystal clear, in a simple overview, what is the IA coverage of key risks etc. in the plan. This will enable the Chief Audit Executive (CAE or head of audit) and other key stakeholders, to evaluate whether audit resources are adequate or not. Black holes in coverage should be made clear so that stakeholders can consider other sources of assurance (whether by lines one or two or using consultants) if IA coverage is not possible.

-

Other considerations - including regulatory considerations and the new GIAS

There are a range of other detailed considerations when developing an internal audit plan that may be influenced by:

- the organisational context (e.g., if an organisation is going through a period of rapid change, or into a new market) or

- because of specific GRC considerations (e.g., the creation of a new compliance function or roll-out of a new risk reporting system) or

- specific legal and regulatory needs (which may result in additional risks but also impose obligations on what an internal audit function does).

In these instances, specialist advice and support may be needed to think through and then map out what these considerations mean for the risk assurance jigsaw in lines 1 and 2 and then the IA plan.

Note that under the old IIA standards, two of the most common areas highlighted as needing improvement during an External Quality Assessment were Audit planning and Assurance co-ordination. And with even stronger requirements in the new IIA GIAS, there is an increased risk that IA teams will have problems meeting the required standards in future.

To proactively manage the risk here, I would strongly urge Heads of Audit (CAEs) to carry out an EQA preparation process (especially concerning the audit plan and assurance mapping requirements) 12-18 months before any formal EQA takes place. This should flush out any gaps and help the IA team build in some of the latest good practices that will undoubtedly develop over the next 1-2-3 years; but most of all, it will head off the risk that a big gap is identified in the IA plan.

-

Developing an internal audit strategy

It should not be a great surprise to learn that many IA teams think about their medium and longer-term (strategic) choices at the time they develop their audit plans. After all, if you want to utilise data analytic capabilities to focus your assignments or look at new areas of the organisation, you may need new skills in the team, or support from an outsourced consultant and/or additional budget.

Reflecting this growing practice for IA teams to think strategically, the IIA GIAS has now spelled out that all IA teams should create an IA strategy. The purpose of an IA strategy is to make it clear and explicit what direction the internal audit function should take in relation to its services (e.g., whether there will be more advisory services, greater use of technology or better root cause analysis of key issues) and to make clear its future needs to support these changes in relation to a) Human Resources, b) Financial resources and c) Technology resources.

The expectation that all IA teams should have a strategy is not saying that every IA team should make big changes or ask for significant extra budget. Rather, it is making it clear that if, for example, the IA team budget is to remain relatively static, what should be the knock-on implications? One answer might be to deploy more lean and agile audit techniques and enhanced assurance co-ordination to ensure the IA team delivers more with less.

Viewed from another perspective, if improvements in GRC take place in lines 1 and 2, this may very well have a knock-on impact on what internal audit does in future, bearing in mind the need to co-ordinate assurances. For example, if the finance function makes greater inroads into automating its activities and strengthens its own checking procedures, this is likely to give some headroom in the IA plan to focus on other areas, rather than carrying on with routine financial controls audits year after year.

In conclusion, IA teams are a precious resource, which need to be focused ever more intelligently on the issues that matter, recognising the three lines model and the need to deliver value and insight. For this reason, the bar is being raised on audit planning and internal audit strategic plans, where there is a growing demand for rigour and transparency around the choices internal audit is making in the short and longer term. Following the letter of the new requirements is one thing, but better CAEs recognise that following the spirit of what is intended is the way to put the IA team on the front foot for the future. Hopefully readers will agree with this.