Part 1 – Basic principles

This article is intended to assist candidates with identifying the South African (SA) tax consequences of emigration to or from South Africa. The intention is not to provide an in-depth discussion, but to draw attention to the various possible tax issues. You should refer to your study text to complement and integrate the aspects covered in this article.

Against the backdrop of emigration, a natural person will inevitably have incurred transactions in different countries; these transactions are often referred to as ‘cross-border’ transactions. It must be determined in which of the countries these transactions may be subject to tax.

The process of emigration involves many decisions and steps. From a financial perspective an individual needs to have a clear understanding of (among others) the tax consequences that will arise. Remember that tax consequences exist/arise for the individual for the periods before, during, and after emigration. You should always read an exam question carefully to determine which of these periods are the focus of the question.

You should also make sure that you are fully aware of the different taxes that are required to be addressed. The easiest way to do this is to make a list of the different taxes and pay careful attention to the names of each. For example, ‘Income Tax’ includes ‘Normal Tax’, ‘Dividends Tax’, ‘Donations Tax’, etc. The arrangement of sections in the Income Tax Act are found at the start of the Act, where they are divided into different ‘Parts’. Other taxes, for example Estate Duty, VAT and Transfer Duty, are levied in terms of separate Acts.

Structured approach to determining SA tax consequences of cross-border transactions

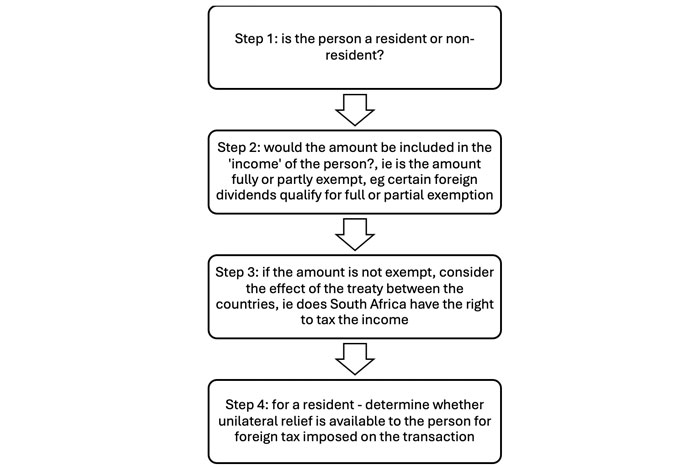

Certain steps are followed to determine the South African tax consequences of cross-border transactions.

Figure 1: The South African tax consequences of an amount derived from a cross-border transaction

As illustrated in figure 1, the tax consequences of cross-border transactions are driven by the tax residence status of the person. Note that steps 1-3 in figure 1 are applicable to both residents and non-residents. Step 4 only applies to residents.

Why is tax resident status important?

The South African tax system is residence-based for South African residents and source-based for non-residents. Residents are taxed on their world-wide income, while non-residents are only taxed on South African source income. The same principle applies when the transfer of wealth is taxed (for example CGT, donations tax and estate duty), with residents being taxed on world-wide assets, and non-residents only on certain of their South African assets (immovable property in South Africa and assets attached to a permanent establishment (PE) in South Africa).

Many sections of the various tax Acts provide for differing tax treatments of transactions for residents and non-residents.

Examples of differences in tax treatment: resident vs. non-resident

Examples of tax items/issues that need to be considered by a natural person contemplating a break in their tax resident status:

- Interest received from a South African source: the first R23 800 is exempt if the person is younger than 65 at the end of the year of assessment. If the person is 65 or older at the end of the year of assessment, the amount changes to R34 500. This exemption applies to both residents and non-residents (unless the interest received by the non-resident is already fully exempt (see below). Due to a recent legislative change, the above limits must be apportioned if a period of assessment is shorter than 12 months, such as the case with emigration.

- Interest from a South African source received by non-residents: the full amount of the interest is exempt, unless

- The non-resident was present in South Africa for more than 183 days during the 12 months prior to the receipt or accrual of the interest, OR

- The debt from which the interest arises is connected to a PE of the non-resident in South Africa.

- Foreign dividends received by South African residents: application of the specific exemption rules that could result in exemption is required (for example the participation exemption where the person holds 10% or more of the equity shares and voting rights). Note that if the resident becomes non-resident, those dividends will not be subject to tax in South Africa as they will be from a foreign source.

- Employment outside South Africa: if the requirements are met (> 183 days outside South Africa, including a period of more than 60 consecutive days) up to R1.25m of a person’s remuneration from an employer may be exempt. This relates to both residents and non-residents; it often happens that individuals are seconded to work in other countries, which may end up in their resident status being broken, if they decide to stay in the other country.

- Lump sums, annuities, pensions etc. received by a resident from a source outside South Africa, in respect of past employment outside South Africa. For example, if a person works for an employer outside South Africa and then emigrates to South Africa and retires here, any lump sums and monthly pensions from their previous employer/ retirement fund may be exempt. When an individual has worked for the employer in the foreign country as well as in South Africa, an apportionment must be done to exempt the portion of the retirement benefit that relates to employment outside South Africa.

- Lump sums, annuities, pensions etc. received by non-residents from South African retirement funds, will be from a South African source and subject to tax in South Africa (see the discussion in Part 3 of this article).

- Certain amounts received by/accruing to non-residents may be subject to withholding taxes that must be withheld by the payer of the amount, and paid over to SARS, resulting in the non-resident only receiving the after-tax amount.

- In most cases, remuneration paid by a resident employer to an employee is subject to the withholding of employees tax. This also applies to non-resident employers with PEs in South Africa.

- If a resident person is a beneficiary of a South African trust and then becomes non-resident, amounts that vest in the beneficiary may in certain cases be attributed to a donor of an asset to the trust.

- Residents who control foreign companies (CFC’s) (ie more than 50% of participation rights) are taxed proportionately on their share of the company’s net income. If a person becomes non-resident, it might have the effect that the company is no longer a CFC, and the person will no longer be subject to South African tax on their share of the company’s net income. However, there will be an exit charge (see Part 3), taxing the shareholder on a deemed disposal of the shares the day before becoming non-resident.

- Residents who have business operations (as sole traders or in partnerships) will decide whether to keep their business operational in South Africa, or to dispose of the business assets. If they decide to keep the business active after the change in their tax resident status, the business will likely constitute a ‘permanent establishment’ in South Africa. Upon emigration there is no ‘exit charge’ on those assets, as they will remain ‘in the South African tax net’ and the income from them will still be taxed, being income from a South African source accruing to a non-resident.

- Transactions between residents and non-residents who are connected persons will be taxed on an arm’s length basis, resulting in possible transfer pricing adjustments. It is always important to consider the connected person definitions in practical scenarios. Individuals are connected to:

- their relatives,

- companies in which at least 20% of the equity shares or voting rights are held, and

trusts of which they are beneficiaries and the other beneficiaries of such trusts.

As emigration usually requires extensive tax planning, care must be taken to understand the relationships between taxpayers that may be involved.

The above list of examples is not exhaustive and many other tax provisions may need to be considered in light of changing resident status.

Role of treaties and double tax relief

Tax treaties between countries aim to eliminate the possibility of double taxation by allocating the ‘taxing right’ on different classes of income to the relevant countries. As illustrated in figure 1, the provisions of the relevant treaty are only applied in step 3. In other words, first determine via steps 1 and 2 whether a specific amount would be subject to tax in South Africa (applying the normal rules). If it would not be so taxable, the treaty does not need to be considered (from a South African tax perspective), as the amount would typically then only be taxable in the other country.

If a taxing right is awarded to South Africa in a treaty, the provisions need to be considered together with the South African tax provisions, with the treaty provisions enjoying preference over the local provisions. It can happen that (despite the tax treaty) an amount is taxed in both countries. Residents of South Africa can claim a tax credit (unilateral relief) where taxes are suffered on foreign source income, both in South Africa and the other country. This is likely to be encountered when an individual emigrates but remains a South African tax resident and also when a non-resident becomes a resident.

An individual who is contemplating emigration will generally be aware of the way in which their income is taxed in their current country (before emigration). The individual will need clarity as to the taxation of income should they move their tax residence to another country (after emigration).

Example

Let’s say Lethabo (47 years old) is a resident, receiving interest from an investment in South Africa. The source of the interest is South Africa (as it is earned from funds applied in South Africa) and Lethabo is therefore entitled to an exemption of R23 800 per year.

If Lethabo emigrates to Greece in the middle of a year of assessment, the interest that accrues during the second part of the year may be fully exempt (if the above requirements are met). Note that this does not mean that the interest received by Lethabo as a non-resident will be tax-free – it is usually subject to a withholding tax – the rate is usually 15%, but in terms of Article 11 of the treaty between South Africa and Greece, the rate is limited to 8%.

In respect of the interest received in the first half of the year, R23 800 is proportionately reduced to R11 900 and is available against the interest received during that period, when he was still a resident.

Part 3 of this article deals with the specific tax consequences arising at the time of emigration (the so-called exit charge).

Part 2 – the definition of 'resident of South Africa' and the taxes affected

This part of the article provides an overview of the concept of ‘resident’ and identifies the various South African taxes that could be impacted by the tax resident status. Note that the tax resident status of an individual needs to be assessed for every year of assessment. While the tax resident status affects the treatment of different aspects of taxation (ie after resident status has already been established), there are also specific tax consequences that arise on the date of change of status (ie when becoming or ceasing to be, a resident (see Part 3).

The definition of ‘resident of South Africa’

The first step is to consider the tax treaty between the person’s previous and new home countries. If the treaty establishes that the person is exclusively a resident of the other country (not South Africa) the treaty provisions override the South African tax provisions, and the person will be regarded as a non-resident for South African tax purposes.

It is only if a treaty provides South Africa with a taxing right, that the South African tax consequences (starting with the residence classification) need to be considered.

It is important to note that the definition of ‘resident’ may be different for different types of taxes.

1. Income Tax (IT)

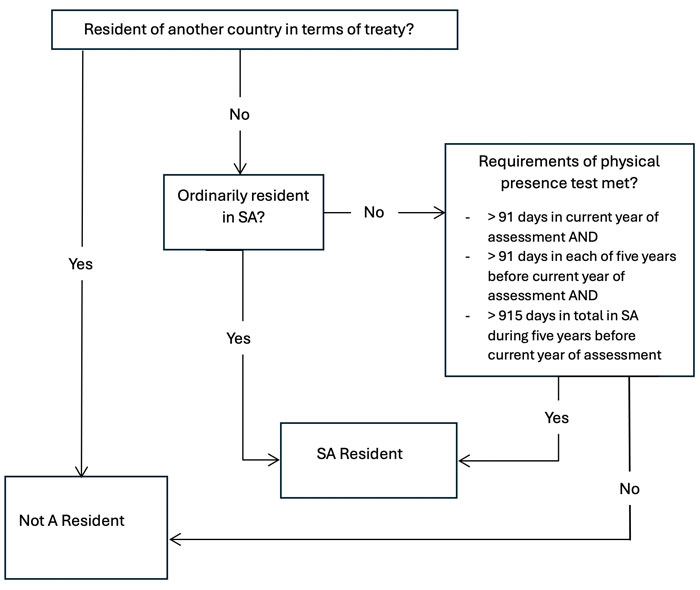

For IT purposes an individual is regarded as a South African resident if they are regarded as ‘ordinarily resident’ in South Africa or if they have been in South Africa for a certain number of days (physical presence test), as illustrated in Figure 2.

Ordinarily resident

The first step is to determine whether the person is ‘ordinarily resident’ in South Africa. Ordinary residence is the place where a natural person has their usual or principal residence – their real home. The person’s individual circumstances (for example their family, friends, business, religious and other social activities) will determine where their real home is located.

If a person formally emigrates from South Africa, they could still be regarded as South African tax residents if there is an indication that they might return in the foreseeable future.

Physical presence test

If a person is not at any time during a year of assessment ‘ordinarily resident’ in South Africa, it could be that their regular presence in the country indicates that they are tax residents in South Africa. This requires that the person is present in South Africa for more than 91 days in the current year of assessment as well as in each of the five years preceding the current year. In total the person must have spent more than 915 days in South Africa during the preceding five years of assessment (the so-called ‘physical presence test’).

Figure 2: Determination of South African residence status

Normal tax

If a person is a South African tax resident, they are subject to tax on their world-wide income. This includes capital gains realised on assets, wherever the assets are situated.

As non-residents are only taxed on South African sourced income and (certain) capital gains, a thorough knowledge of the source rules prescribed by legislation and common law principles is required. The source of income and capital gains/losses is generally connected to the location of the underlying asset; however, certain specific rules could apply and need to be identified.

Payments of certain amounts to non-residents (eg royalties and interest) could be subject to withholding tax at specific rates. Although these rates are provided in the South African legislation, they might be limited in treaties between South Africa and other countries.

Dividends tax

In general, only dividends declared by South African companies are subject to dividends tax at 20% (subject to certain exclusions). If a dividend in specie is distributed by a South African company, the tax is levied on the company; in other cases (such as cash distributions) the tax is levied at shareholder level and withheld by the company. The residence status of a shareholder does not affect the liability for the tax. Therefore, if an individual emigrates and becomes non-resident, they will still be subject to dividends tax on dividends from SA companies. The rate of dividends tax in respect of dividends paid to non-residents may, however, be limited in the treaty between South Africa and the other country.

Donations tax

Property donated by South African residents may be subject to donations tax at 20%. Various specific exemptions and an annual exemption of R100 000 apply, but if a person is planning to donate assets prior to emigration, the accompanying donations tax liability may be substantial. Bear in mind that CGT may also be payable on assets donated by South African residents.

It should be noted that non-residents are not subject to donations tax, not even in the case of immovable property in South Africa. However, CGT may be payable on the donation by non-residents of immovable property and PE assets in South Africa. The definition of resident as outlined above is also applicable here.

2. Estate Duty (ED)

Estate Duty is levied at 20% of the net estate of a person who is ordinarily resident in South Africa at the date of their death. Note that there is no physical presence test for Estate Duty purposes. The net estate will include world-wide assets, although certain deductions are available in the calculation of the Estate Duty liability at death.

Persons not ordinarily resident in South Africa are subject to Estate Duty on all their South African property.

A thorough study of the Estate Duty principles is essential to understand the possible liability for this tax. Exam questions often require that candidates consider the Estate Duty consequences if a person should die today, and it is an essential part of the estate planning process.

3. Transfer Duty (TD)

This tax is payable on the acquisition of residential property in South Africa. Although payable by the purchaser at the rates specified in the Transfer Duty Act, it is often necessary to take its effect into account when residential property is transferred in anticipation of emigration decisions. Remember – if a property is subject to VAT, there will be no Transfer Duty payable.

Transfer Duty is payable (where applicable) by both residents and non-residents.

4. Value Added Tax (VAT)

As part of the emigration process a natural person will consider whether any business activities in South Africa will be ceased or continued. If the person is a VAT vendor and decides to sell/cease an enterprise, output tax may be levied on the supply/deemed supply of goods in respect of which an input tax deduction was claimed. Under certain circumstances the enterprise may be sold as a going concern and could qualify to be zero rated.

The VAT provisions are extensive and require a thorough understanding to integrate their consequences into the emigration decisions.

Part 3 – change in residence status

Parts 1 and 2 of this article dealt with the tax consequences that need to be considered in terms of income and capital once an individual’s tax resident status has been determined.

This part of the article focuses on the impact of a change in tax residence status on the taxes identified in part 2.

As a result of the different treatment of residents and non-residents, assets owned by a taxpayer will, depending on the case, either move into, or out of, the ‘tax net’ on immigration. This is because residents are generally taxed on their world-wide income and assets/property (regardless of source) while non-residents are only taxed on their South African sourced income and assets.

Becoming a tax resident

- If a person immigrates to South Africa and their true intention is that South Africa will be their permanent home, they will be resident from the day of becoming ordinarily resident (ie the day they arrive in South Africa) until the last day of the year of assessment.

- If a person is deemed to be a resident due to the physical presence test, they will be deemed to be a resident from the first day of the year of assessment (ie 1 March). However, if they leave South Africa for a period exceeding 330 days, they will cease to be a resident from the day of their departure.

Upon becoming a tax resident, a person’s assets are deemed to have been disposed of at their market value on the day before becoming a resident and to have been re-acquired on the day of becoming a resident. This is subject to certain exclusions (such as immovable property in South Africa and assets of a PE in South Africa). As the person would have been a non-resident until the date of immigration, they will not be subject to tax on the disposal, but a base cost will be established for those assets, as they are now ‘brought into the net’.

Ceasing to be a tax resident

In this case the person is deemed to have disposed of their assets to a resident at their market value on the day before ceasing to be a resident. This could result in capital gains/losses on capital assets, as well as recoupments of previously granted tax allowances (ie assets used for trade purposes). For trading stock, a deemed disposal will lead to a normal tax event and the full market value of the stock will be included in gross income.

The above resulting tax consequences are referred to as an ‘exit charge’. Certain exceptions to the deemed disposal rule are provided for (generally assets that remain ‘in the tax net’):

- Immovable property situated in South Africa

- Assets connected to a PE of the person after the change in tax residence

- Restricted equity instruments that have not yet vested before the change in residence.

As residents’ world-wide assets are subject to tax, their foreign assets are also deemed to be disposed of – the market value of such assets must be determined in the same currency in which they were acquired.

When a person emigrates from South Africa and they belonged to a South African retirement fund (pension, provident or retirement annuity fund), they will need to consider how they choose to receive their fund benefits. The following options are available:

- Leave their accumulated fund benefit in the fund and only receive the benefits at the normal retirement age. Lump sums and pensions (annuities) will be from a South African source and included in gross income in the year of retirement. Lump sum benefits will be taxed in accordance with the more favourable lump sum benefit tax table.

- Take one third of the accumulated fund benefit as a lump sum and the rest as monthly annuities. The lump sum will be subject to tax at the less favourable lump sum withdrawal tax table. The same gross income principle as above will apply.

- Take the entire accumulated fund benefit as a lump sum – in this case the emigration must be recognised by the South African Reserve Bank for exchange control purposes and the person must remain a non-resident for an uninterrupted period of three years. The lump sum can therefore only be taken three years after emigration, and it will be subject to the less beneficial lump sum withdrawal tax table.

If there is a change in tax residence status during a year of assessment, it could mean that a person is regarded as a resident for a part of the year of assessment and as a non-resident for the rest of the year. This would require separate tax calculations for the periods before and after change in residence. Note that the deemed disposal of assets referred to above, is taken into account in the final period before the change in residence.

The following limits, exemptions and rebates are reduced proportionately between the period before and after change in residence:

- Annual interest exemption (either R23 800 or R34 500).

- Annual retirement fund contribution limit of R350 000.

- Annual contribution limit to tax-free investments of R36 000.

- Annual capital gains tax exclusion of R40 000.

- Primary, secondary and tertiary tax rebates.

In scenarios where natural persons either immigrate to, or emigrate from, South Africa, their underlying circumstances need to be considered to determine what their true intentions are with regards to tax residency.

Example:

Sue is a 45-year-old South African tax resident who emigrated to Australia on 30 June 2024. She resigned from her employment and does not intend to return to South Africa in the future, as her entire family resides in Australia. She has accumulated a sizable member’s reserve in her employer’s provident fund and has elected to receive the full benefit as a lump sum.

Sue owned the following assets on 30 June 2024:

- A primary residence in Cape Town which she has been letting to tenants since her emigration.

- Shares in South African companies, which she still holds as capital investments.

- A holiday apartment in the French Riviera which she still currently owns.

From a seemingly short set of circumstances, many tax consequences flow. In an exam the required discussions are specified (eg ‘discuss the Estate Duty consequences’), while in other cases you could be expected to address multiple aspects (eg ‘discuss ALL the tax consequences’). Ensure that you discuss the specific types of taxes that are required.

Brief explanation of the current and future tax consequences for Sue:

- Sue’s intention is clearly to break all ties with South Africa. The facts seem to indicate that she will cease to be ordinarily resident from 1 July 2024 and she is therefore regarded as a resident from 1 March 2024 until 30 June 2024 and as a non-resident from 1 July 2024 until 28 February 2025. Although she will have two ‘years of assessment’ for 2025, she will only be entitled to one primary tax rebate.

- The provident fund lump sum will only be paid out on 1 July 2027. The less favourable lump sum withdrawal tax table will be applied on that date. The lump sum is deemed to be from a South African source.

- The primary residence will not be deemed to be disposed of on emigration (immovable property in South Africa). It will retain its original base cost and upon its eventual disposal will be subject to CGT in South Africa. The source of the capital gain would be in South Africa as that is where the property is located. South Africa has this taxing right in terms of Article 13 of the treaty with Australia.

The purchaser of the property at that point must withhold tax of 7.5% from the proceeds and pay that over to SARS on Sue’s behalf (unless the proceeds are less than R2m). This would be a pre-payment of her final South African normal tax liability for the year of disposal, and she will need to complete a tax return for that period. She can approach SARS for a directive if certain criteria are met.

The source of the rental receipts will similarly be South Africa and therefore subject to normal tax in South Africa. This is in line with Article 6 of the treaty.

If the above capital gain and/or rental is subject to tax in Australia, she will not be entitled to the foreign tax credit, as she will not be a resident of South Africa anymore. Unilateral tax relief in such a case must be sought from Australia in terms of Article 23 of the treaty.

- The shares in the South African company are deemed to have been sold at their market value on 30 June 2024 and are immediately re-acquired for the same market value. As the shares are held with capital intent, the disposal will result in a capital gain/loss, depending on their base cost. Future dividends received by Sue will be included in her South African gross income but exempt from normal tax. Dividends tax will be withheld by the South African companies. Although the usual dividends tax rate is 20%, the rate will be limited to 15% in terms of Article 10 of the treaty. No South African unilateral tax relief applies, as she will be a non-resident and the dividends are exempt anyway.

- The holiday apartment is deemed to be disposed of at its market value on 30 June 2024, as world-wide assets are subject to tax. As the property would have been acquired in Euros, the market value will be expressed in Euros. The property is immediately deemed to be re-acquired at the same market value. Upon its eventual disposal it will not be subject to South African taxation, as Sue will be a non-resident and the source of the asset is in France.

- Capital gains/losses (both on the deemed disposals above and any ACTUAL disposals between 1 March 2024 and 30 June 2024) will be aggregated and subject to an annual exclusion of R40 000. A resultant net capital gain will be included in her taxable income at 40%, or in the case of a net capital loss, carried forward to the next year of assessment.

- If Sue should die before selling any of the above assets, the residence and shares will be subject to Estate Duty in South Africa at 20%, after an abatement of R3.5m. The holiday apartment in France will not be subject to Estate Duty as she would be ordinarily resident in Australia.

If she dies before the pay-out of the provident fund benefit, it will not be subject to Estate Duty as retirement benefits are specifically excluded from property.

Additional note

The rules regarding tax residence are different for natural persons and non-natural persons (such as companies). While this article explored the basic rules applicable to the tax residence status of natural persons before and after their emigration, it should be noted that such persons could also be involved in the management of a corporate entity such as a company. A change in the effective management of the company (as a result of the change of residence of an individual) could also lead to the company becoming or ceasing to be non-resident, and to the company being subject to certain tax consequences as a result. As a natural person could have an interest in such a company, this could also affect their overall financial situation and emigration decisions.

Written by a member of the ATX-ZAF examining team