During 2018, Malta transposed into Maltese tax legislation the provisions of Council Directive 2016/1164 issued on 12 July 2016 (commonly referred to as Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive, ATAD I). Some of the provisions of ATAD I and II are included in the ATX-MLA syllabus and are examinable from June 2020 onwards, with two exceptions which are explicitly excluded:

- The anti-hybrid mismatch rules within Malta’s transposition of ATAD II, and

- The Equity-Escape Carve-Out (Regulation 4(5), S.L. 123.187) in the Interest Limitation Rules

This is one of three articles on this topic and explains the controlled foreign company (CFC) rules. The other two articles explain the interest limitation rules, general anti-abuse rules (GAAR) and exit tax. Candidates should note that the content of these articles indicate the extent to which the provisions of Malta’s transposition of ATAD I and II are examinable at Strategic Professional (ie ATX-MLA) level.

1. CFC rules

The principal objective of the CFC rules is to bring to tax in Malta, the profits which are artificially shifted by a Maltese taxpayer to a foreign controlled company. The CFC regulations are applicable as from the basis year starting on or after 1 January 2019.

The CFC rules provide that an entity or permanent establishment (PE) of a Maltese company whose profits are not subject to tax or exempt from tax would be considered as a CFC if both the following tests are satisfied:

(a) Control test

In the case of an entity, the Maltese taxpayer by itself or jointly with its associated enterprises1:

(i) either holds directly or indirectly more than 50% of the voting rights, or

(ii) owns directly or indirectly more than 50% of the capital, or

(iii) is entitled to receive more than 50% of that entity’s profits.

If during the CFC tax year, there are changes in the direct and indirect participation in the voting rights, ownership of capital and entitlement to profits, the CFC rules will apply only for the period or periods during which the control test was satisfied.

The tax guidelines, issued by the Commissioner for Revenue, explain in further detail the anti-fragmentation2 rule, which aggregates the direct and indirect interests of the taxpayer together with the direct and indirect interests of any associated enterprises, so as to ensure that the economic reality is reflected. Therefore, the associated enterprises’ direct and indirect participation in the voting rights, ownership of capital and entitlement to profits should be attributed to the respective taxpayer’s participation in the voting rights, ownership of capital and entitlement to profits in the foreign company.

Candidates are expected to be familiar with the anti-fragmentation rule example in section 10.2 of the Commissioner for Revenue’s Guidelines in relation to the Anti-Tax Avoidance Directives Implementation Regulations.

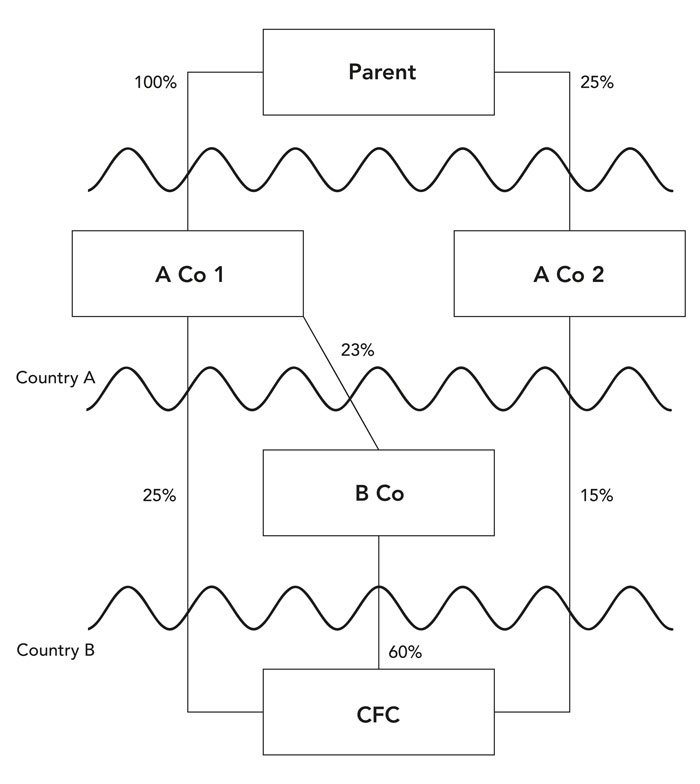

The following example, taken from the Commissioner for Revenue guidelines, illustrates the application of the above-mentioned approach. In this regard, the percentages captured in this example show the percentage holdings of ownership.

- A Co 1 holds a direct interest of 25% in the CFC.

- In line with the above-mentioned principles, A Co 2 is an associated enterprise of A Co 1. This in view of the fact that A Co 1 and A Co 2 are owned in common by a Parent which has a direct participation of at least 25% in the respective entities. As explained above, the 15% direct interest of A Co 2 in the CFC shall be attributed to A Co 1.

- The Parent is an associated enterprise of A Co 1 since the entity holds a 100% participation in A Co 1. Nevertheless, indirect interest of the Parent in the CFC both through A Co 1 and A Co 2 are not counted to ensure there is no double counting.

- A Co 1 also holds a further indirect interest of 13.8% (23% of 60%) through its holding of B Co.

Therefore, A Co 1 holds an effective Controlling Interest of 53.8% which means that the minimum Controlling Threshold is satisfied through the application of the anti-fragmentation rule. In this regard, there is no need for the exercise to be re-computed on the basis of voting rights and entitlement to profits since the test has been satisfied in respect of the rights of ownership of capital.

AND

(b) Low-tax test

Where the actual corporate tax paid by the foreign entity or the PE on its profits is lower than the difference between:

(i) the tax that would have been charged on the entity or the PE under the Income Tax Act3 in Malta, and

(ii) the actual corporate tax paid on its profits by the entity or the PE.

The ‘actual corporate tax paid’ shall be deemed to mean corporate tax paid or borne, whether by way of withholding or otherwise, and without regard to the jurisdiction in which such income and/or corporate tax was suffered. The Commissioner for Revenue guidelines clarify that, ‘actual corporate tax paid’ shall not take into account any deferred tax assets and liabilities recognised in the entity’s financial statements.

However, it is to be noted that any PE of a CFC of the taxpayer, that is not subject to tax or exempt from tax in the jurisdiction of the CFC should not be taken into account.

Candidates are expected to be able to apply both tests to a given scenario and explain when a non-Malta entity would satisfy the CFC definition and when it would not.

2. Implications of triggering the CFC definitions

When an entity or a PE satisfies the conditions to be treated as a CFC, the Maltese taxpayer is required to include in its tax base, the non-distributed income of the entity or PE, arising from non-genuine arrangements, which have been put in place for the essential purpose of obtaining a tax advantage.

The rules provide that an arrangement or a series thereof are to be regarded as non-genuine to the extent that the entity or PE would not own the assets or would not have undertaken the risks which generate all, or part of, its income if it were not controlled by the Maltese companies, and where the significant people functions relevant to those assets and risks, are carried out in Malta and are instrumental in generating the controlled company's income.

A non-genuine arrangement is defined in such a manner as to require a factual analysis of the arrangement. In this regard, it is necessary that the taxpayer understands the role played by itself and the CFC respectively. In general, the more important the role a party plays, the more attribution of profits will arise to that party. This underlying rationale of the arm’s length principle corresponds to what would usually happen between independent enterprises taking part in any type of business activities. Unless directed otherwise by the Commissioner for Revenue, the authorised OECD approach constitutes a valuable source of interpretation for the purposes of a correct characterisation of the significant people functions. It should be noted that the significant people functions focus on the physical presence of persons performing the functions.

ATX-MLA candidates are not expected to be aware of the authorised OECD approach and the significant people functions beyond the level of detail given above. However, candidates are expected to be able to point out when a CFC’s income appears to arise from non-genuine arrangements. A typical example would be a Maltese company having a subsidiary in a zero tax or very low tax jurisdiction, which derives a significant proportion of the profits derived by the group, without having any assets or employees, especially when it is clear that the functions that generate such profits are carried in and from Malta.

Should the above analysis ascertain that the CFC operates through a non-genuine arrangement, it needs to be determined further whether the essential purpose of the CFC is intended to obtain a tax advantage. The CFC income to be included in the tax base of the Maltese taxpayer is limited to amounts generated through assets and risks which are linked to significant people functions carried out by the Maltese controlling company.

3. CFC carve outs

However, there are few exceptions to the CFC anti-abuse provisions, as per below:

- Where the entity or the PE derives accounting profits of not more than €750,000 and non-trading income of not more than €75,000;

or

- Where the accounting profits of the entity or PE do not exceed 10% of the operating costs4.

4. Computation of CFC income

The CFC income to be included in the tax base of the Maltese taxpayer must be calculated in accordance with the arm's length principle, and in proportion to the Maltese taxpayer's participation in the CFC. The taxpayer shall ensure that sufficient documentation is maintained to enable it to determine the profits/loss of the CFC in terms of the Income Tax Acts.

To the extent that a CFC prepares its financial statements based on accounting standards not identified in the Accountancy Professions Act, then adjustments would need to be made in order to bring such financial statements in line with any accounting standard as sanctioned by the Accounting Professions Act before applying the provisions of the Income Tax Acts.

Non-distributed income for a basis year shall mean the income of the CFC as calculated in terms of the CFC rules, less the profits derived during that year distributed up to the tax return date.

The CFC income shall be included in the tax period of the Maltese taxpayer in which the tax year of the CFC ends. Where the CFC distributes profits to the Maltese taxpayer, and those distributed profits are included in the taxable income of the Maltese taxpayer, the amounts of income previously included in the tax base must be deducted from the tax base when calculating the amount of tax due on the distributed profits, in order to ensure there is no double tax.

If the Malta taxpayer disposes of its participation in the entity or of the business carried out by the PE, any part of the proceeds from the disposal previously included in the tax base of the Malta taxpayer shall be deducted from the tax base when calculating the amount of tax due on those proceeds, in order to ensure there is no double tax. Moreover, there shall be allowed a double tax relief credit (calculated in accordance with the provisions of articles 77 and 82 of the Income Tax Act and therefore including a credit for underlying tax) of the tax paid by the entity or PE against the tax liability of the Malta taxpayer.

It is the aim of the examining team to assess candidates’ knowledge of how CFC income is brought to tax, through application of knowledge to a given scenario. Candidates will usually be expected to present their answers in the form of explanation with supporting calculations.

Written by a member of the ATX-MLA examining team

Footnotes

(1). An ‘associated enterprise’ is defined as:

(a) an entity in which the taxpayer holds directly or indirectly a participation in terms of voting rights or capital ownership of 25% or more or is entitled to receive 25% or more of the profits of that entity;

(b) an individual or an entity which holds directly or indirectly a participation in terms of voting rights or capital ownership in a taxpayer of 25% or more or is entitled to receive 25% or more of the profits of the taxpayer.

If an individual or entity holds directly or indirectly a participation of 25% or more in a taxpayer and one or more entities, all the entities concerned, including the taxpayer, shall also be regarded as associated enterprises.

(2). In simple words, the process whereby shares in a non-Maltese entity are held through both direct and indirect holdings in order to attempt to fall below the 50% threshold.

(3). The tax that would have been charged in Malta means the tax as computed according to the Income Tax Acts. Therefore, all income arising in the CFC jurisdiction shall be deemed to be arising in Malta. Income arising outside of the CFC jurisdiction shall be deemed to be income arising outside of Malta.

(4). Operating costs may not include the cost of goods sold outside the country where the entity is resident, or the PE is situated, for tax purposes and payments to associated enterprises.