1 Unit

CPD technical article

In the fourth article in his series on international business, Tony Grundy explains how alliances can add real value

First published in the October 2014 UK edition of Accounting and Business magazine.

Studying this technical article and answering the related questions can count towards your verifiable CPD if you are following the unit route to CPD and the content is relevant to your learning and development needs. One hour of learning equates to one unit of CPD. We'd suggest that you use this as a guide when allocating yourself CPD units.

Along with international development and acquisitions, alliances are a key area of corporate development on top of more conventional, organic development. An alliance is a formal or informal partnership between two or more organisations to achieve their common goals through co-operation, commitment and potentially the joint management of resources.

An alliance can thus take the form of a co-operative understanding through to a joint agreement and then on to setting up an organisation, potentially a separate legal entity. Alliances can thus take the form almost of ‘50 shades’, and this flexibility is both very attractive and common in today’s fluid markets.

In this article we look at the pros and cons of organic development versus acquisitions versus alliances. We then examine the different roles and kinds of alliances that might be available, and also how to evaluate these.

Swipe to view table

| Pros | Cons | |

|---|---|---|

Organic |

Generally lower risk Less demanding Typically less complex |

Perceived to be slower Demands more patience Often inadequate to fill the ‘strategic gap’ |

| Acquisition | Fast to do deal Often offers a bigger-value prize Gives control |

Integration can be hard and take longer Is medium to high risk Can be time-consuming and distracting |

| Alliance | Lower risk than an acquisition Gives competences that you may lack Low investment |

Less permanent, shorter life-cycle May dilute competence and cover up weaknesses Can be hard to manage, especially with change |

Organic, acquisition or alliance?

The table above plots some of the generic pros and cons of these three avenues to corporate development. They appear to be equally balanced with little to choose between them. In reality, they will be very different. For instance, while ‘organic’ may seem less attractive as it is slow, this is possibly because there are restricted investment resources, or because no one has thought very imaginatively about how to do it faster, better or differently - which leads us back to the ‘cunning plan’ of our first series of articles. This would also be a reason why it didn’t - on its own - fill the ‘strategic gap’.

Acquisitions may seem quick - but only if you are skilled at integration. If this goes sour it will take longer, and possibly fail. Generally, acquisitions also destroy value - principally as the seller has better information than the buyer.

Equally, alliances may seem an attractive third and middle way, but over time the agendas - business and personal - may shift and the co-operation at the start may crumble. So each needs to be evaluated as part of the entire pool of corporate opportunities at the time.

Different roles

Alliances may play a whole range of roles - some more strategic than purely operational. Typically they can be targeted at:

- blending skills in a way otherwise not possible - thus generating a fresh capability and competitive advantage

- creating a new and distinctive product

- preparing to meet or create a new market opportunity

- knowledge transfer - open or covert - from your partners to you and vice versa

- funding and resourcing a new business

- pooling existing resources to meet demand more easily and with greater critical mass

- achieving lower costs

- being able to charge a higher price and share that enhanced margin

- enabling the partners to have a common understanding that there will be ongoing mutual business to be shared between them - provided that the market is there and that the partners perform - giving stability for all (an ‘operational alliance’)

- the predatory acquisition of another partner’s customer base, or learning sufficiently from them to be able to compete in that same market once the alliance has run its course

- once the venture has become well established, squeezing the other partners through price rises that they cannot resist as they have lower bargaining power.

These different objectives add value in different ways - through sales volumes, price, cost, leveraging investment or skills.

In short, there may be a huge array of reasons for entering alliances, some of which are potentially competitive if not unsavoury, eg predatory behaviour or squeezing partners. For example, I touched on Rover and Honda in my last article - by 1994 it was said that Honda had grown so big and strong in that partnership that it had Rover in a ‘financial bear-hug’.

Types of alliances

There are a number of different types of alliances that we can characterise as:

- informal partnerships

- formal partnerships

- distributor relationships

- supplier agreements

- franchises

- joint ventures

- limited companies.

It is helpful at this point to distinguish between strategic and tactical alliances. I define a strategic alliance as an alliance opportunity which enables its value to last for at least a three-year time horizon.

A tactical alliance is an alliance opportunity which enables its value to be realised within what is likely to be no more than a three-year time horizon.

I have chosen a three-year time horizon because in most industries this is a foreseeable time period of market conditions and it is usually within the competitive advantage period (CAP).

Alliances span a spectrum of time horizons, styles of organisation and management, and, potentially, legal forms too. Typically in more mature markets there comes a point where the established industry structure is too rigid to optimise the industry value chain and collaborative opportunity exceeds competitive need; this is the most important test for alliance strategies. Where there is a value-adding activity that cannot easily be optimised by a separate competitor, but may be able to be by more than one with highly complementary skills, then a strategic alliance opportunity exists.

In my own business (strategy consulting and executive development) I have never been successful in establishing an alliance with a larger strategy consultancy; there is too much overlap of competencies. But I’ve had two successful alliances with brand strategy experts and a board-level coaching company, which have been win-win.

In executive development as a regular supplier I have had both tactical and strategic alliances with training providers and also with business schools.

The optimal economic model is for these companies to do the front-end marketing and provide venues etc, but where a full-time employment model is not economically desirable for them and where suppliers like myself wouldn’t want that as it is constraining.

Another condition of success is that there is sufficient symmetry of interests.

I was once involved as a startup partner in a turnaround company at the beginning of the credit crunch. There were four of us. After a few months one of the partners was poached to be CEO of a company needing full-time turnaround, so we lost our ‘centre-forward’.

The three of us limped on with me as the strategy man, a financial director-type and a lawyer. I will confess that I didn’t go all-out as I was unsure whether we would ever score and there was an imbalance of time being invested by the three of us.

Often an alliance’s fate will be determined by the equal commitment - or otherwise - of the various partners.

Evaluating alliances

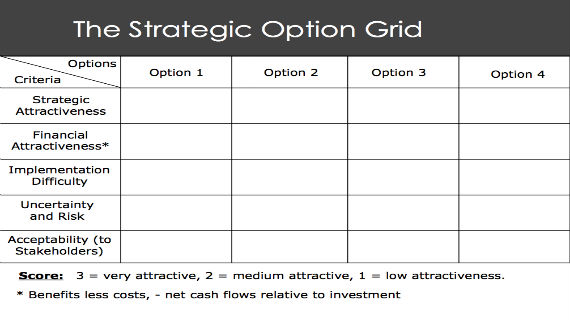

Once again I would like to prescribe the strategic option grid as an excellent mechanism for evaluating alliances. Here, the five criteria (as explored in earlier articles) are:

- strategic attractiveness (of the market opportunity, the alliance’s competitive position, and the structural and skills and bargaining power parity within the alliance)

- financial attractiveness

- implementation difficulty (setup, development adaptation and change, and possible dissolution)

- uncertainty and risk (short, medium and long-term)

- stakeholder acceptability (visualising possible changes over time over the evolution of the alliance).

As far as financial attractiveness is concerned, this isn’t just about profitability or even net cashflows. You need to be mindful of the impact on any exit value for your business. Alliances may not be what a new owner wants or will pay for. In that respect an alliance can be like putting a new kitchen in your house - a good part of that cost will never be recovered on sale.

So like any long-term relationship where you don’t actually get married, alliances can add value, but they have their pros and cons and need managing.

Dr Tony Grundy is an independent consultant and trainer, and lectures at Henley Business School

1 Unit