1 Unit

CPD technical article

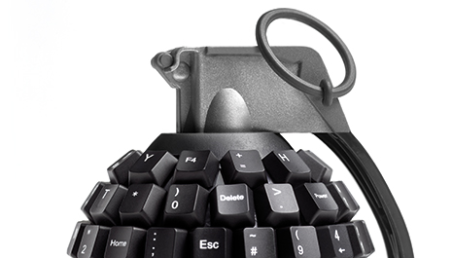

Technology can help improve performance but to think that it can replace a sound corporate strategy is a dangerous delusion, says Greg Satell

Studying this technical article and answering the related questions can count towards your verifiable CPD if you are following the unit route to CPD and the content is relevant to your learning and development needs. One hour of learning equates to one unit of CPD. We'd suggest that you use this as a guide when allocating yourself CPD units.

This article was first published in the November/December 2016 international edition of Accounting and Business magazine.

Tribune Publishing, an icon of American journalism, recently renamed itself Tronc (Tribune Online Content) and released a video to show off a new ‘content optimisation platform’, which Tronc’s chief technology officer, Malcolm CasSelle, claims will be ‘the key to making our content really valuable to the broadest possible audience’ through the use of machine learning.

As a marketing ploy the move clearly failed. Instead of debuting a new, tech-savvy firm that would, in the words of chief digital officer Anne Vasquez, be like ‘having a tech startup culture meet a legacy corporate culture’, it came off as buzzword-laden and naive. The internet positively erupted with derision.

Yet what is even more disturbing than the style is the substance: the notion that you can transform a failing media company – or any company in any industry for that matter – by infusing it with data and algorithms is terribly misguided. While technology can certainly improve operational performance, the idea that it can replace a sound strategy is a dangerous delusion.

Data downside

First, let’s take the notion of data-driven content optimisation. The basic idea is to mine behavioural data from a company’s websites and external providers to predict what customers might want to read. Armed with that knowledge, you can place the right links in front of the right people, get them to click more often and increase the customer base.

Yet data is no panacea. Our online behavioural information represents but a small fraction of what drives our preferences. In the case of Tronc, news is a fast business, making it very hard – if not impossible – to effectively personalise recommendations. So it is unlikely that content optimisation will improve user experience.

That’s why content optimisation models tend to aggregate data among large subsets of users. By playing the averages, a smart algorithm can increase click rates on websites and social media significantly. This, most probably, is what Vasquez meant when she said that the firm plans ‘to harness the power of our local journalism, feed it into a funnel, and then optimise it so we reach the biggest global audience possible’.

The problem with this approach is that it tends to result in a feedback loop. Algorithms are not agnostic but tend to favour certain types of article over others. Before you know it, you are judging your audience’s preferences on the basis of assumptions you’ve embedded into the system. At that point, you’ve lost editorial control to a data-driven mirage.

Another troubling aspect is Tronc’s continual use of the terms ‘machine learning’ and ‘artificial intelligence’, which Vasquez says will allow journalists to automate more mundane tasks, like searching for photos. Tronc investor Patrick Soon-Shiong also asserts that the technology will allow the company to make thousands of videos a day.

Both statements are surreal. Are we really to believe that the key to the future of media is a Google image search? Or that all we need to wow audiences is to scrape together more videos by automating the process? Even more disheartening, however, is that the focus of these efforts seems to be on the production process – meaning the mechanical aspects of publishing text and image online – rather than helping journalists originate, report and develop stories.

A more thoughtful approach to an artificial intelligence platform might comb through the company’s resources to produce condensed dossiers on sources, including the contact information of Tronc reporters who have interviewed those sources before. A slightly more sophisticated system could suggest potential sources for a story using much of the same data.

But there doesn’t seem to be any thought given to empowering journalists to become more informative or to serve their audience better. Rather the focus of this new digital effort seems to be on automating the production process to cut costs and then upselling readers to higher-margin video content.

Eyeballs over experiences

A third troubling aspect is that the goal of Tronc’s digital efforts seems more geared to collecting eyeballs rather than creating experiences. Rather than working toward a truly new model for publishing that would be more rewarding for readers, the firm hopes that through digital wizardry it can get the same articles it already publishes in front of more people.

Clearly, this is not a new idea. Publishers like BuzzFeed and Vice News mastered the art of content optimisation long ago. Since then, there has been no shortage of imitators spamming our social media feeds with listicles and hip videos. It’s hard to see how adding a louder voice to the cacophony will achieve anything.

Tronc bills its new strategy as ‘the future of journalism’, but if anything its shiny new digital strategy seems mired in the recent past. In fact, it’s an approach that digital pioneers have already moved on from. BuzzFeed recruited a top-notch news team, while Vice News has done hard-hitting, documentary-style reporting in places like Ukraine and North Korea. Others, like Politico, have created new niches by focusing on more in-depth reporting.

Managing for metrics rather than mission

Finally, the greatest delusion of all is that optimisation itself can create a sustainable competitive advantage. If all it took were algorithms and machine learning, we would expect IBM or Google to dominate multiple market sectors. Tronc, with little technology expertise to speak of and no money to invest in significant research, will be betting its future on third-party software. Yet somehow it still expects to gain a leg up on competitors by tweaking conversion rates and adding video content. That’s not a strategy; it’s a mirage.

The company is failing to address the fundamental questions it is facing: what is the role of a newspaper business in a digital media environment? How can we use technology to empower our journalists to collaborate more effectively and further our editorial mission?

The role of a great publisher is not to predict what readers may want to consume, but to help them form their opinions through strong, authoritative journalism. You win in the marketplace not by chasing readers with algorithms but by attracting them with a superior product. Yet great journalism can’t be automated, because it is among the most human of endeavours.

The truth is that Tronc is managing for metrics rather than for mission. So far, at least, it has shown no interest in serving its customers better or enabling its staff to do anything they couldn’t do before.

Greg Satell is a US-based business consultant

1 Unit

CPD technical article

"The greatest delusion of all is that optimisation itself can create a sustainable competitive advantage"